For those of you recreating in a deep, stable snowpack, the words “scary moderate” go together as improbably “donuts” and “wellbeing.” Ski with any frequency in the shallow and pissed-off snowpack of the Rockies, though, and chances are you have some idea what scary moderate means.

For those of you recreating in a deep, stable snowpack, the words “scary moderate” go together as improbably “donuts” and “wellbeing.” Ski with any frequency in the shallow and pissed-off snowpack of the Rockies, though, and chances are you have some idea what scary moderate means.

And therein lies the rub, as they say. The term suggests something; it’s shorthand for a broader concept. In many situations, this is just fine. We use shorthand labels all the time. Sketchy dude. Tweaky knee. Gloomy day. I get it.

The problem with scary moderate is that misunderstanding the concept or not fully thinking it through is the first step in getting myself killed while skiing. In truth, it hints at something we should all understand on a deeper, fundamental level. So I say to you — banish the term from your limitless intellect and abundant vocabulary!

CMAH

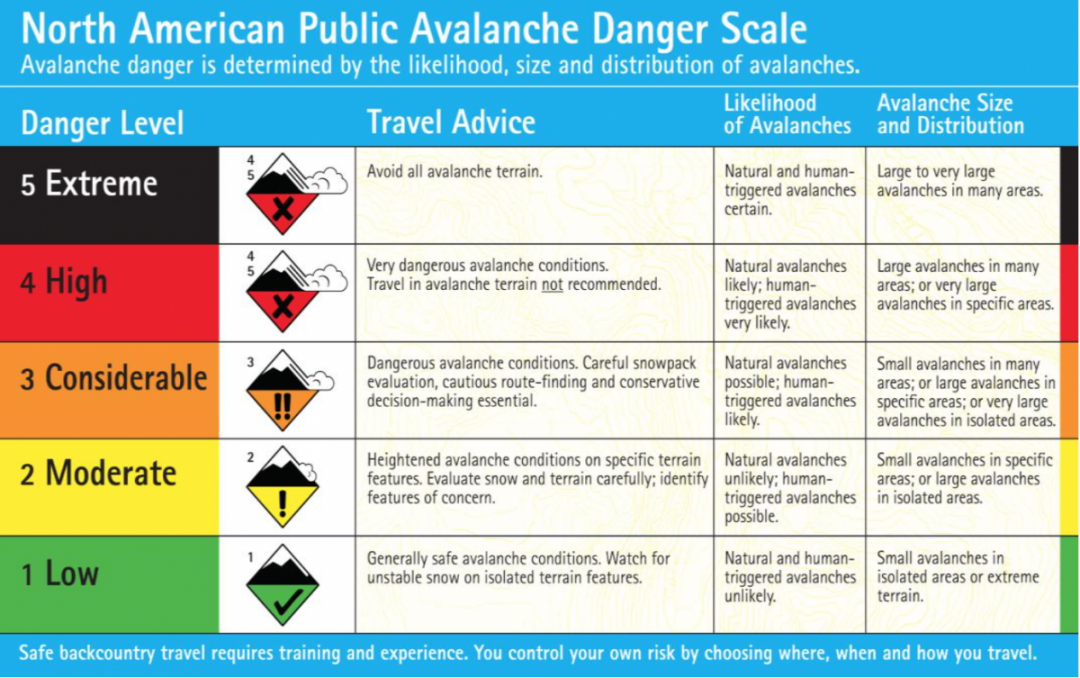

If you’re spending your workday surfing WildSnow (stickin’ it to The Man!), then I trust you’re familiar with the North American Danger Scale — the green-yellow-orange-red-black scale rating avalanche hazard into five levels: low, moderate, considerable, high, extreme. We can debate the nuance and merits of the scale itself (that’s another post or two entirely), but let’s stick with what we have.

You might know most forecasters in the United States and Canada rely on an academic paper, “A Conceptual Model of Avalanche Hazard,” (CMAH), first discussed at the International Snow Science Workshop in 2010, as the foundation for creating their daily forecasts. (It’s easily retrievable online, so click through or track it down if you’ve not read it.)

The North American Danger Scale.

Reading the CMAH paper will greatly increase a user’s understanding of danger ratings and how forecasters arrive at them. Integral to this understanding is recognizing the danger rating on the day is merely one component — and probably not the most important component at that — of the day’s forecast.

In addition to the danger rating, of course, we have:

-nine “avalanche problem types”

-the likelihood of triggering (distribution of the problem x sensitivity to triggering=likelihood)

-destructive potential

-and location.

In summary, we have the danger rating, the overall avalanche problem capturing the above bullet points, and the textual description.

Simple, right?!

Not So Fast

Putting all these factors together while tracking weak layers over time, and updating the forecast with the latest meteorological events on a daily basis makes for a complex task. There is no quantifiable formula, either — ultimately the forecasters must make a final, subjective call on the forecast.

Consider likelihood as a range of probabilities. Moderate, for example, means natural avalanches are unlikely, and human-triggered ones are possible. Considerable, or level 3 or orange, indicates naturals are possible and human-triggered are probable.

Possible versus probable? There’s quite a range of likelihood within those descriptors, a good dose of uncertainty already complicates the danger rating. Add to this location, destructive size, and other subtle factors like the timing of a storm, for example, and it’s a maddening task to arrive at any sort of simple forecast on the day. And then do it again tomorrow. Still interested in that forecasting job?!

Avalanche Problem Types

Luckily for us, perspicacious academics and visionary mountain pros give us another means to make sense of the forecast, as long as we’re listening. The nine “avalanche problem types,” broken into three main categories, allow us to derive more context from the bulletin.

“Storm” problems — loose dry, wind slab, storm slab — are generally present during or immediately after … you ready? A storm. Woh! This is easy!

“Wet” problems — loose wet, glide cracks, wet slab — are usually associated with … drum roll, people, warming, and rain. Ding-ding-ding, we have a winner! Hot damn, I’m getting good at this.

And lastly, you won’t believe this, but “persistent” problems (deep-persistent slabs and persistent slabs) form in old snow and tend to hang around for a long time … they persist in the terrain. And didn’t I say this was complicated? It sounds so simple!

Cornice falls … you noticed I missed one, eh? I’ll let the hive debate whether or not cornices are most associated with storms or wet problems, but you can probably argue it either way. I’d go wet, personally, but those things tend to grow and fall off during prolonged, stormy wind events, too, so take your pick.

But What About Scary Moderate?!

So the CMAH incorporates a bunch of elements to arrive at a forecast and a danger rating. Still, If you’ve read the paper and/or understood my blathering thus far, you can see that simply saying “it’s a moderate” day or answering “considerable” when your buddy asks what the danger rating is, misses crucial information contained in the full forecast.

A recent accident and fatality involved a group receiving only the danger rating and avalanche problems on the day — the textual description was not communicated to the group, and in the end, they triggered an avalanche in terrain described in the bulletin. The text portion of the forecast on the day of the 2013 Sheep Creek accident (six involved, five killed) perfectly described the terrain in which the avalanche occurred.

In short, understanding the forecast requires understanding the danger rating, the problems, and reading/digesting the textual information, too.

Something deep and persistent lurked in Upper Cheap Scotch creek, near the Sorcerer Lodge in BC.

And at long last, we’ve come full circle to scary moderate. Scary moderate typically describes a “low-probability, high-consequence” situation like an avalanche bulletin involving a deep-persistent slab. Chances are you won’t trigger it, but if you do, you’re probably done for.

(Some forecasters use the term “spooky moderate” in a slightly different context, just FYI. That’s another rabbit hole for another time. And for a professional’s take on scary moderate, check out Brian Lazar’s excellent blog post here.)

So why isn’t the danger rating considerable or high when people might get killed in avalanches? Remember that CMAH involves likelihood — how widespread is the problem and how sensitive to triggers is it?

As a persistent weak layer gets buried or begins to heal, the likelihood of triggering goes down, but often the destructive potential goes up. A layer of facets buried 20cm deep can only produce a relatively small avalanche. Get another 150cm of snow on top of that and it might start to heal slowly and my svelte little body (read: puny and weak) has less chance of triggering it, but if I do manage to trigger it, there’s a bunch more snow available to slide down the slope and bury, injure, or kill me. Lower likelihood of triggering, but larger destructive potential. Scary.

Recall, too, that there’s no simple formula for determining the overall danger rating. Forecasters don’t assign a number to each component, for example, and then simply total them to arrive at a danger rating.

Rather, they determine the danger rating only after considering likelihood, size, and location. So a moderate rating with wind slabs is a far different beast than a moderate rating with a deep persistent slab. One is easy to predict and avoid, while the other is difficult to predict, hard to identify in the terrain, and fails in surprising ways.

OK, Get to the Point, Dude

The punch line? The point of all this virtual caterwauling?

People use scary moderate as a shorthand for these low-probability/high-consequence events, and for some of us, it works. My hesitation is if the average backcountry user or avy instructor uses the term, it overemphasizes the danger rating to the detriment of appreciating the problem on the day and the nuance in the rest of the forecast. Saying “scary moderate” as shorthand for what should be a deeper discussion sets that person up to treat all moderate days the same … which they most certainly are not.

Understanding that several different situations can lead forecasters to call the day moderate primes us to go beyond just the day’s rating/color/level. Just as we don’t use a beacon without a shovel and a probe, perhaps we should normalize including the problem and “bottom line” of the forecast when mentioning the danger rating. Danger-problem-text. Beacon-shovel-probe.

For example, if we keep the CMAH in mind, we recognize that a deep persistent problem that’s very difficult to trigger, but might produce a size 4, could qualify as a moderate day (low likelihood, super-high consequence, isolated on certain features). The same forecaster, under different conditions, might also call a widespread, super-sensitive windslab only producing size 2’s moderate, as well—same forecaster, same danger rating, vastly different situation.

I certainly don’t mean to imply the danger rating comes down to one kook in the office, all her biases at play, and excessive uncertainty. On the contrary, I know the Colorado folks have a state-wide video conference each morning, so the entire team can arrive at a consensus, address blind spots, and in the end collaborate on the forecast. There are a bunch of checks and balances built into the system — but to be sure, the system is not a mathematical formula or immune to subjectivity.

Isolating a weak layer in the snowpack.

So the bottom line, for me, becomes whether or not we non-forecasters should be throwing around shorthand terms like scary moderate? I tend to avoid using it on avalanche courses and in writing, simply because it denies the reader or student a deeper understanding of what it entails.

If the Norse god of hunting and snow, Ullr, made me king of the backcountry or even better, an Instagram influencer, I would banish the term from Facebook groups, level 1 avalanche courses, and skintrack banter amongst bro-gnars.

But with an audible sigh of relief from the readers of Wild Snow I am not a king, nor any sort of influencer, but merely a middle-aged mountain guide with a bit of a muffin top and the occasional soapbox from which to deliver febrile rants directed at an audience of people wishing they were out skiing instead of internet’ing.

So take my advice for what it’s worth. It’s nothing more than a non-binding suggestion to at least consider uttering the term scary moderate in a select crowd, one that understands the shorthand you’re using.

Rob Coppolillo writes articles, blogs, and books from his home in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. He’s also an internationally licensed mountain guide and the owner of Vetta Mountain Guides. Connect with him @vettamtnguides on Instagram or here in the comments.

Rob Coppolillo is a mountain guide and writer, based on Vashon Island, in Puget Sound. He’s the author of The Ski Guide Manual.