The layup room is where the pieces of the puzzle all come together before getting glued, pressed, and stamped. You can see the unique ski press in the background of this shot. In the foreground there is a layup in progress.

This past spring, a local DPS employee mentioned their new skis — the Pagoda Tour Series — would be built entirely in Salt Lake City. The company had localized ski production into a single warehouse (aside from bending metal edges, which happens just down the street). DPS feathers the border between a small and large scale ski manufacturer. They have all of their facilities under one roof here in the U.S., but they ship their skis around the world and have gained global recognition.

After a healthy amount of inquiry/pestering, I was invited down to see how the Pagoda Tour skis are made: from rough cut wood plank beginning to snow slashing finish.

DPS: Past

DPS first entered the ski industry spotlight when they made the first ever carbon fiber sandwich ski in 2005. Not to mention when their newly released Wailer 112 RP started turning heads with its new-age, banana-esque look. They now produce a gamut of ski shapes and constructions for all the flavors of skier preference: from playful powder boats to fall line chargers. You might have noticed a slew of acronyms and DPS codewords adorning their topsheets. Those letters denote the shape and construction. Before we get into the factory visit, I’ll shed some light on what they mean.

There’s a striking resemblance here. One is a paradigm-shifting powder ski, the other is a healthy snack.

Shapes

The primary shapes that DPS create are the RP and C2. The RP stands for Resort Powder and is a five-point shape that moves the widest part of the tip and tail closer to the middle of the ski. It’s a lively, pivoty shape that mixes a healthy amount of tip and tail rocker with a short turning radius. This shape can easily ‘slarve’ turns (the beautiful slash-carve) and bounce in and out of snow like a deep powder porpoise.

The C2 (Chassis 2) is a more all-mountain, traditional shape that uses a longer effective edge, more traditional camber and larger turning radius. The C2 is a reliable, predictable ski that will make you feel like a deep-turn-carving rockstar. DPS also makes the Lotus (powder surfing) and Koala (freestyle) shapes that we won’t get into too much detail about. Check them out for more specific stylistic changes. From shape, you can then branch out to a few different DPS constructions.

Constructions

The two prominent constructions that influenced the Pagoda Series were the Tour 1 and the Alchemist. The Tour 1 is an ultralight carbon fiber touring ski that holds a phenomenal surface area-to-weight ratio. The Alchemist is an all-mountain carbon fiber ski designed to be the perfect 50/50 backcountry/resort hybrid. The Tour 1 and the Alchemist stand at two opposite ends of ski touring construction: uphill and downhill oriented [respectively]. The Tour 1 is featherweight, but takes on characteristic carbon chatter when put into variable snow. The Alchemist is solid and damp, but brings with it added weight for the uphill.

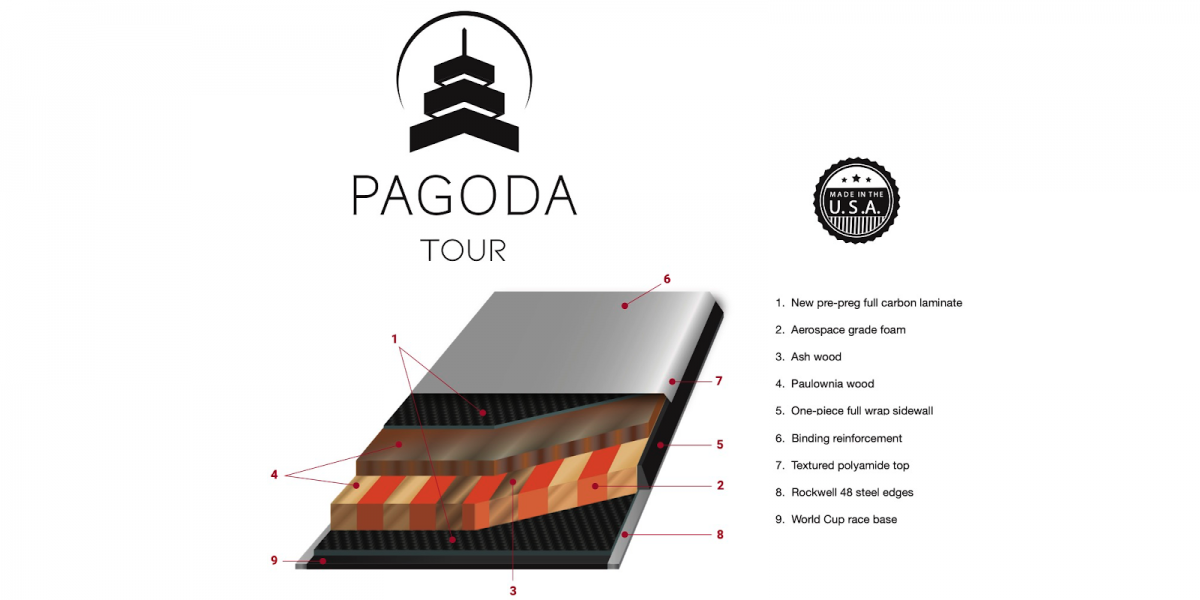

The Pagoda Tour is a culmination of lessons learned from these two constructions. Merging the ultralight Tour 1 with the stable Alchemist. The Pagoda Tour is a step forward in carbon fiber ski construction. DPS created new techniques to make a lightweight, yet robust backcountry touring ski, and all to our benefit, cheers team. So with that brief debrief into DPS jargon, let’s get to know DPS, their factory, and their new Pagoda Tour ski line.

DPS: Present

After eight years of overseas manufacturing, DPS moved their facilities to Utah in 2013. This fall, I went to visit their newly restructured space in the Granary District of Salt Lake City. From the front door of their offices, you can easily check snow coverage throughout the Wasatch. Inside their front door was the Marketing and Administrative office. It was an open office with skis and poles just as present as desks and filing cabinets. Behind another door was the manufacturing facility that produces DPS’s advanced carbon skis.

Alex Hunt (Marketing and Communications Manager) was my tour guide through the factory. Turns out Alex and I have mutual friends through his many years spent guiding in Silverton (quintessential example of the small small world of backcountry skiing). He walked me through each room where the skis are manufactured, explaining each step of what goes into making a pair of the new Pagoda Tour skis.

Constructing the Core

The first step for building the Pagoda Tour, and any ski for that matter, is building the core. Raw materials are received at a loading bay and organized onto shelves. This specific core is a combination of Ash, Paulownia and aerospace grade foam. Ash is a dense wood that provides rigidity for the ski. Paulownia is much lighter than ash and brings with it weight savings benefits. Adding aerospace-grade foam gives the ski improved dampening that counters the snappy energy of carbon fiber. The foam demonstrates a recursive theme with the Pagoda Tour. DPS has struck a chord with their carbon fiber skis by balancing the carbon liveliness with other techniques and materials that bring dampening and stability — all without adding excessive weight.

The first room of the construction process is the core room. Wood and foam are laminated and layered into blanks. The blanks get cut in a 3D CNC mill to get their shape, profile, and pour-in sidewall.

DPS layers the core materials with a traditional sandwich lamination, but in multiple vertical orientations. This creates a vertically laminated core of ash, paulownia and foam rather than individual horizontal layers of each material. The vertical orientation adds more labor and precision to building the core, but increases rigidity with the same amount of materials. DPS’s core innovation is adding multiple layers of vertically laminated core material at different grain orientations to provide even more rigidity and energy for (roughly) the same material use. The name Pagoda comes from this construction technique. A Pagoda is a tiered shrine commonly found in western Asia (check out the Pagoda logo). The ski is layered like a Pagoda, with a unique vertically laminated and horizontally layered construction.

The multi-layered core is then milled to give the ski its length and shape, and receives its pour-in sidewall. Plastic is heated up and injected into the circumference of the ski to create a single sidewall. The continuity of the sidewall installation can better absorb energy and creates a more durable ski. Once this process is finished, the core looks like a fancy 2” x 36” plank with a pair of skis drawn on top with melted plastic. During the final stage of the milling process, the Pagoda Tour’s profile is created and excess material is trimmed. These are brought into the next room to be layered with the rest of the materials that make up the ski.

Layering the Layup

The Pagoda Tour layup showing the Pagoda-inspired ‘vertically laminated horizontally layered’ construction.

The Core is received next door where the ingredients for the Pagoda Tour sandwich are put together. The recipe is as follows (from bottom to top):

— Ultra High Molecular Weight polyethylene (UHMW) base with a tacked-on Rockwell 48 metal edge

— Proprietary pre-impregnated carbon fiber weave

— Vertically laminated core of ash, paulownia and aerospace grade foam

— Another layer of vertically laminated ash for good measure

— Another layer of proprietary pre-impregnated carbon fiber weave because more carbon means more rad

— DPS’s signature textured polyamide topsheet with a HDPE mounting plate underneath

The layup room is where the pieces of the puzzle all come together before getting glued, pressed, and stamped. You can see the unique ski press in the background of this shot. In the foreground there is a layup in progress.

This stack of materials is glued together with layers of epoxy resin; painted in between like frosting in a layer cake. After the sandwich is set, it gets pressed in a high pressure, high temperature oven to receive its final profile. The result is a rectangular DPS Pagoda Tour Monoski. The crude monoski gets moved down the line to The Splitting Room. Here, the skis are finally split into their destined two-planked glory.

Splitting the Skis

The Splitting Room was capitalized for unsolicited dramatic effect. This room consists of a few industrial bandsaws and belt sanders. They cut and sand the individual skis out of their single pressed molds.

Alex looked at me here and said in a dramatic tone, “This is where the twins are split.” That stuck with me.

The skis then receive a high end factory tune at this stage. Belt sanders refine the skis shape and base. A few high end machines then put structure into the base and edges. Now the skis resemble…skis! Perfectly tuned and ready to rip.

The finishing room is where the ‘twins are split’ and refined to a skiable condition. After that edges are sharpened and bases are structured before getting sent for inspection. Here a base structure is being put into a freshly split twin.

Finishing the Product

Each pair of skis gets passed through a finishing room where they are inspected under bright light on a familiar-looking tuning bench. After passing inspection, skis are mounted and PHANTOMed and shipped off to their new mountain homes — be it Hokkaido, Japan or a few miles away in Little Cottonwood Canyon.

The final gatekeeper of quality control is the inspection table. After this, the skis are ready to get shipped out the door.

The Pagoda Tour line up consists of five different models. After the factory tour, I asked Alex if he could archetype each size for the Wildsnow community. Apologies Alex if I put you on the spot here. Each model is denoted by its waist wide and shape:

The 112 RP is the Pivoty Powderboat

The 106 C2 is the Do-It-All Jack-Of-All-Trades

The 100 RP is the Agile Couloir Technician

The 94 C2 is the Mountain Tool

The 87 C2 is the Long Mission Machine

Are these crass generalizations or digestible categorizations? You decide, because ultimately these are recommended use cases, not rules. Want to use the 87 C2 as your all season, lightweight touring ski? Do it. Can the 112 RP be a ‘Mountain Tool’? Sure. That’s the beauty of backcountry skiing: you define your own rules. However, I find it helpful to get DPS’s design intent distilled into one proper noun declarative. These skis will be shipped out across the world to be skied up and down all different kinds of mountain terrain. Hopefully they have one common thread: putting big ol’ smiles on skiers’ faces in the process.

DPS: Future

A big takeaway that I took from the DPS facilities is to strive for excellence as a process, not an end goal. DPS will never make the ‘perfect backcountry touring ski’, but they’ll keep striving towards that goal every single day.

See our previous DPS coverage

Shop for DPS skis

Slator Aplin lives in the San Juans. He enjoys time spent in the mountains, pastries paired with coffee, and adventures-gone-wrong. You can often find him outside Telluride’s local bakery — Baked in Telluride.